LIFF screening Saturday November 7th 1400.

A memorable film from the 1950s Hindi Cinema. “Producer and director Guru Dutt’s intensely original film [The Thirsty One] is widely considered one of India’s unquestionable classics, striking a chord with its vision of the romantic artist in conflict with an unfeeling materialistic world.” (Cinema Ritrovato Catalogue, 2014).

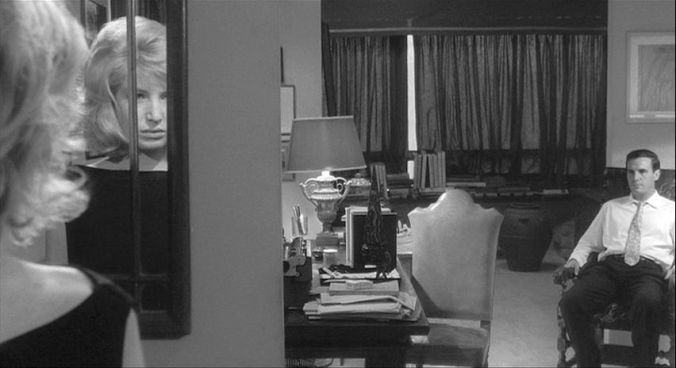

Guru Dutt also appears in the film as the poet Vijay, opposite Mala Sinha as Meena and Waheeda Rehman as Gulab. The film has a distinctive use of music and songs and exemplary black and white cinematography with fine use of crane shots. The music is by Y. G. Chawhan and the cinematography by V. K. Murthy. Dutt’s collaboration with these two artists and with the cast and production team offers a control of sound and image that stands out in the period.

Pyaasa is among a number of films from The Golden Age of Indian cinema, [late 1940s and 1950s] which have been restored and made available in either 35mm or digital versions by the recently established Film Heritage Foundation. The films offer the pleasures of the distinctive Indian musical film form. They combine melodrama and emotion with great dance and musical sequences. Pyaasa is in Academy ratio and runs 143 minutes. So this is a rare opportunity to see not just an Indian classic but an outstanding film of World Cinema.